A lip tie is an extra-tight or thick upper lip frenulum (the tissue connecting the upper lip to the gum) that restricts normal lip movement. In infants, a lip tie can make breastfeeding or bottle-feeding challenging. However, mild lip ties are common and often harmless. This article explains what a lip tie looks like, how to recognize one in a baby or toddler, and when treatment (often a quick frenectomy) is needed. We cover symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options (including frenotomy/frenectomy), plus long-term concerns. Throughout, we use the primary keyword lip tie and related terms (e.g. lip tie baby, upper lip tie, frenectomy for lip tie) naturally.

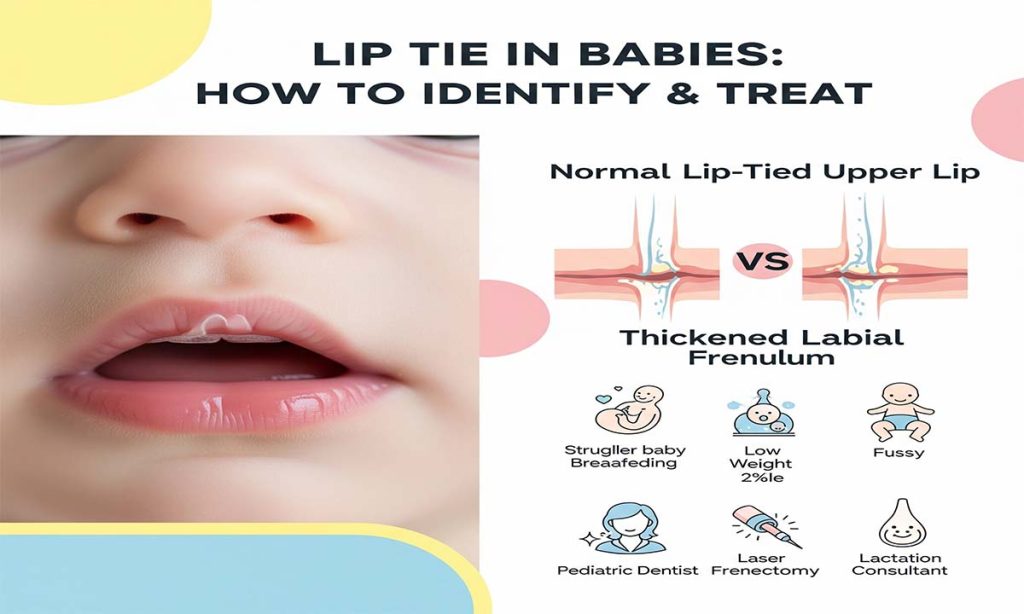

All babies have a fold of tissue under the upper lip called the maxillary (superior) labial frenulum. As shown above, this labial frenulum is normally present and can vary in size. A lip tie occurs when this membrane is unusually tight, thick, or attaches very close to the upper gum, preventing the lip from flanging (turning out) properly. In other words, the upper lip is effectively “tied” down. (In contrast, a tongue tie involves the tissue under the tongue.) A lip tie in babies is not dangerous if the baby feeds and grows well. Most infants with a lip tie will adapt or outgrow it. But if a lip tie is causing problems (like poor latch or slow weight gain), a simple surgical revision – typically called a frenotomy or frenectomy – can free the lip and resolve symptoms.

Table of Contents

What Is a Lip Tie? (Anatomy and Definition)

In normal anatomy, the maxillary labial frenulum is a midline band of mucous tissue connecting the inner upper lip to the gums. This frenulum stabilizes the lip but usually allows full range of motion. When this tissue is unusually thick, short or tight, it may restrict the upper lip. This restriction is called. Specifically, a lip tie is diagnosed if the frenulum’s tightness limits the lip’s ability to flange outward or leave the gumline (e.g. when suckling).

According to pediatric otolaryngology literature, the point at which a normal frenulum becomes a “tethered” upper lip (lip tie) is not clearly defined. In fact, one review notes: “the typical versus atypical appearance of this frenulum is not known. Nor is it known whether this frenulum has any functional consequences”. That means clinicians rely on functional assessment (movement and symptoms), not just appearance.

Experts sometimes use classification scales (like the Kotlow system) to describe lip ties. For example, Kotlow’s classification defines Class 1 as a mild attachment near the gum, up to Class 4 as a very tight frenulum that severely limits lip mobility. (In practice, Class 1 may have no significant restriction, whereas Class 3–4 often cause symptoms.) Figure below illustrates how a lip tie is graded in some systems:

- Class 1: Frenulum attached slightly above the gumline (often no restriction).

- Class 2: Frenulum attaches midway on the gum, moderate restriction.

- Class 3: Frenulum flexible but can be tight; symptoms may occur.

- Class 4: Frenulum attaches high on the gum/base of nose, severely limiting lip flange.

In many cases, babies manage well even with a lip tie, because growing tissues sometimes loosen naturally. By about 6–12 months, the frenulum often becomes less prominent as the lip’s range improves. Research shows that the frenulum “becomes much less obvious as children get older,” and there is no clear evidence that clipping a lip tie in infancy improves breastfeeding. In fact, La Leche League advises that if an infant is feeding comfortably and gaining weight, no lip tie intervention is needed.

Still, when a frenulum is so tight that it truly impedes lip motion, babies may develop feeding problems. Lip ties are generally less common than tongue ties (ankyloglossia), but often both occur together in a baby. Some evidence suggests lip and tongue ties may run in families (i.e. have a genetic component), though their clinical significance is still debated.

Symptoms and Signs of a Lip Tie

A lip tie baby may show feeding difficulties early on. Common signs include breastfeeding or bottle-feeding problems, such as:

- Poor latch or slippage: Baby struggles to flange the upper lip around the breast or nipple. The lip may stay tight or roll in.

- Clicking sounds: A “click” at the breast or bottle indicates air leakage due to a loose latch.

- Very long or fatiguing feeds: Baby falls asleep or tires easily during nursing because of inefficient sucking.

- Choking or gagging: The baby may cough, choke, or gasp if the latch is not stable.

- Slow weight gain: Insufficient milk transfer can lead to slow or inadequate growth. (All infants with feeding concerns should have weight monitored.)

- Persistent fussiness or colic: Some babies with lip (or tongue) ties are gassier or colicky due to swallowing extra air.

In one large review, difficulty breastfeeding was cited as the most common sign suggesting an upper lip (or tongue) tie. For example, a baby might slide off the nipple during nursing or be unable to maintain suction. The baby’s upper lip may not flange outward and seal well on the breast, so the latch is shallow.

Symptoms can also be seen on the mother’s side during breastfeeding:

- Nipple pain or damage: Mothers may experience pinching pain, abrasions or blisters on the nipple from a baby with a poor latch.

- Engorgement or mastitis: If feeding is inefficient, milk may build up, causing engorgement, plugged ducts or mastitis after feeds.

- Low milk supply: Chronic nursing problems can make it hard to establish adequate milk production.

It’s important to note, however, that many feeding issues blamed on have other causes. Breastfeeding specialists emphasize that many factors (nursing position, latch technique, tongue-tie, prematurity, etc.) contribute to difficult feedings. In fact, authoritative sources point out “there is no evidence or agreement that a is an important factor” in most breastfeeding problems. While severe upper lip ties can theoretically make a seal harder, lip and tongue ties account for only a small subset of feeding issues.

Key takeaway: Watch for latch problems, milk transfer issues, or slow weight gain. If these occur without obvious cause, a lip tie may be involved. However, the presence of any upper lip frenulum by itself is not abnormal – only a tight, restricting one (with symptoms) is considered a lip tie.

Lip Tie vs Tongue Tie (Oral Ties)

A tongue tie (ankyloglossia) involves the frenulum under the tongue; a lip tie involves the tissue under the upper lip. They can occur alone or together as “tongue cases. Because both limit oral movement, many of their effects overlap. For instance, both can cause similar latch problems and clicking during feeding. In fact, lip ties are much less common than tongue ties, but when they coexist it makes feeding especially challenging.

When evaluating a baby, a provider will check for both tongue and lip ties. It’s possible for a baby to be tongue-tied but not lip-tied, or vice versa. Many experts recommend treating significant tongue ties before (or along with) because tongue restriction often has a bigger impact on feeding. But if the upper lip tissue is also tethered, releasing both (lip and tongue) may give the best outcome.

The terms are commonly used interchangeably by parents and practitioners. Some providers refer to combined cases with the acronym TOTs (Tethered Oral Tissues). Because of this overlap, we will sometimes mention tongue ties (ankylglossia) when discussing it, especially when considering breastfeeding and speech outcomes.

Diagnosing a Lip Tie

There is no standardized test or measurement for lip tie; diagnosis is clinical. A pediatrician, dentist, lactation consultant (IBCLC), or ENT specialist will visually inspect the baby’s mouth during feeding. Key observations include how easily the upper lip can move and flange out of the way when the baby sucks. If the lip cannot lift and cover the lower gum because the frenulum is too tight, it is considered a it. During an exam, the clinician will gently lift the upper lip to see how high it reaches and if blanching (paleness) occurs on the gum – blanched tissue means tension on the frenulum.

Many clinicians use a grading or classification system (such as Kotlow’s) when recording a lip tie diagnosis, although evidence suggests the exact grade does not always correlate with symptoms. A recent study points out that “there are no standard measurements for the diagnosis” and that lip tie assessment varies widely among providers. Therefore, context is crucial: if the baby feeds well and gains weight normally, a tight frenulum alone isn’t labeled a problem. Only when the frenulum restricts function (flanging, nursing latch) do we call it a true lip tie.

As a practical rule: any newborn with breastfeeding issues (especially persistent latch problems or weight loss) should have a feeding evaluation. In such cases, the examiner will check for both lip ties and tongue ties. If a found alongside feeding difficulties, it may be recommended for revision.

How to Feed a Baby With a Lip Tie

Before and after any treatment, proper feeding technique is important. Some mothers find that a baby with a lip tie can feed more easily from a bottle than the breast, because bottle nipples can sometimes compensate for latch problems. If breastfeeding is painful or ineffective, expressing milk (hand or pump) and feeding by bottle can ensure adequate nutrition.

Lactation consultants recommend positioning and latch strategies to help a baby with a lip tie. For example:

- Ensure a deep latch: Hold the baby’s nose to the breast and make sure the baby takes a wide mouthful of areola (not just the nipple).

- Use a laid-back feeding position or “biological nurture” position to let gravity assist latch.

- Shape the breast in a “sandwich” (compress the breast horizontally) so the nipple is more elongated and easier for the lip to grasp.

- For bottle feeding, try different nipple shapes that encourage the baby to use the lips and tongue effectively.

In general, good positioning and a deep latch can often overcome minor lip or tongue ties. One breastfeeding support source emphasizes that the baby’s top lip does not need to flare out excessively for successful nursing; rather, it should simply rest neutrally against the breast. If the latch remains shallow or painful, it is wise to consult a specialist (IBCLC or pediatric dentist) for a thorough assessment.

Treating a Lip Tie (Frenotomy/Frenectomy)

When a true lip tie is causing significant feeding problems or poor growth, a quick surgical procedure can release the tight tissue. Two related terms are used: frenotomy (snipping or cutting the frenulum) and frenectomy (removing or releasing it, often with a laser). In most practices for infants, the treatment is a simple office procedure:

- The baby’s upper lip is lifted, and the frenulum is cut or ablated using sterile scissors, electrocautery, or a soft-tissue laser.

- The procedure is very fast (seconds long) and typically causes minimal pain. Infants usually cry more from restraint than from the cut itself. Because the frenulum has few nerves and blood vessels, there is little bleeding and often no need for stitches.

- Many providers note that no sedation or anesthesia is required for a lip tie release in a very young baby. (The La Leche League reports that lip tie revisions cause almost no pain and are often done without any anesthesia. In contrast, tongue ties sometimes require topical numbing or a quick injection, especially in older infants.)

- After the snip, the incision typically heals on its own with simple care. Some doctors recommend gently stretching or massaging the area a few times daily (for example, have the parent press on the incision with a clean finger) to prevent the frenulum from reattaching too tightly.

Does it work? Research on lip tie release is still limited. Some reviews conclude that evidence specifically for lip ties is lacking. For example, one analysis noted there is “little evidence at this point that a frenectomy for lip tie improves breastfeeding”. However, more recent studies show promising results in properly selected babies. For instance, a 2017 study of over 200 infants (with various ties) found that frenotomy “greatly improve[d] breastfeeding outcomes, with nearly immediate effects”. A 2023 case series at the University of Texas reported on seven babies with isolated upper lip tie and feeding difficulty: after surgical release, all seven infants gained weight, and every mother reported easier, more effective nursing. In that series, the average weight gain per week almost doubled post-procedure, and none of the babies needed additional intervention.

These positive findings suggest that for babies who truly struggle with feeding due to a, treatment can help. It’s important to have a thorough evaluation (often including observing a feeding session) before surgery. A lactation consultant or pediatrician can confirm whether the lip tie is indeed the main issue. In some cases, improving technique or treating a co-existing tongue tie may be enough without surgery. But if a lip tie is deemed to significantly impede latch or weight gain, releasing it is a quick fix with low risk.

Frenectomy for Lip Tie: Modern pediatric dentists and ENTs may use a diode or CO₂ laser for lip tie release. The laser can seal tissue as it cuts, virtually eliminating bleeding. Clinics often market laser frenectomy as almost painless and faster-healing. Regardless of tool (scissors vs. laser), the goal is the same: remove the tight section of frenulum to allow full lip mobility. The term frenectomy usually implies more complete removal (sometimes needed if the frenulum is very broad), whereas frenotomy often means a simple snip. Both terms appear in parents’ searches (e.g. “frenectomy for lip tie”). Ultimately, the details depend on the practitioner’s preference.

Aftercare and Recovery

Immediately after the procedure, most babies can breastfeed or bottle-feed right away. The soothing effect of nursing often calms them quickly. Any minor discomfort usually subsides rapidly. Parents should follow any specific instructions given by the doctor. Common aftercare tips include:

- Lip massage/exercises: Use a clean finger or cotton swab to gently stretch the upper lip outward several times a day for the first week or two. This keeps the tissue from healing back together. Some practitioners provide illustrated exercises for parents to do.

- Pain relief (if needed): Over-the-counter infant acetaminophen can be given if the baby is fussy, but most infants do not need it.

- Oral hygiene: Keep the area clean. Breast milk itself has healing properties, so frequent nursing is good. Some doctors suggest using a saline rinse after feeds or applying a tiny amount of antibiotic ointment (as prescribed) to prevent infection.

- Monitoring feeding: Keep an eye on breastfeeding after release. Often the baby’s latch will improve right away. Continue frequent feedings; mothers may notice better milk drainage and less feeding pain soon after.

- Follow-up check: A 1–2 week follow-up is common to ensure healing is proceeding and to reinforce exercises.

It’s worth emphasizing: there are generally no scar or growth issues after a lip tie release. A published case series showed no cases of the frenulum “re-tethering” on its own during follow-up. By a few weeks post-op, the incision usually heals into a smooth gum line. The baby’s upper lip should then be able to move normally.

For breastfeeding mothers, many report that pain decreases and the baby latches more easily after the tie is released. In the 2023 UTMB study, 100% of mothers said nursing was subjectively easier after the procedure. One year later, most babies still had weight and feeding on track, suggesting lasting benefit. That said, some babies learn new latch habits gradually, so continued support from an IBCLC can help ensure optimal feeding patterns.

Lip Tie in Toddlers and Later Childhood

By age 1–3 years, even an untreated lip tie often stops causing problems, because the lip and gum tissues mature. However, in older infants and toddlers, an untreated tight frenulum can present as:

- Persistence of a gap (diastema) between front teeth: A very tight lip tie can force the front teeth apart as they erupt.

- Food or object trapping: If the lip cannot lift enough, food particles might collect under the tie, making brushing the front teeth tricky. This may increase risk of early cavities between the front incisors.

- Speech or oral habits: In theory, a very tight upper lip could affect articulation of certain sounds (like “f” or “th”) later on. However, most speech issues are due to tongue rather. The consensus is that speech delays from lip ties alone are uncommon. Proper dental evaluations occur anyway when speech concerns arise.

- Gum irritation or infection: In rare cases, if food consistently rubs under the lip tie, the gum tissue could become inflamed. This usually resolves if the tie is released.

Overall, most toddlers with mild lip ties grow out of any effects. If feeding and dental development are normal, many pediatric dentists will simply observe. If dental spacing or hygiene issues occur, they may recommend release at that time.

In summary, lip tie problems later in life are generally limited. According to one mother-support article: an untreated “may” create a gap between teeth and make brushing difficult (leading to caries), but even experts note many adults live with lip ties almost symptom-free. The main reason to fix in a toddler (beyond infancy) would be if it interfered with oral hygiene or if orthodontists need to close a front-tooth gap by moving the teeth together.

Summary and Call to Action

Lip ties can look alarming on close inspection, but remember: most upper lip frenula are normal and harmless. A true lip tie is one that actually limits movement and causes feeding or dental issues. If your baby or toddler has trouble nursing (or holds frustration with bottle-feeding) and no other cause is found, ask your pediatrician or lactation consultant to check the upper lip. A simple exam (often during a feeding) can diagnose a significant lip tie.

If an upper lip tie is confirmed and is affecting feeding or growth, a quick frenotomy/frenectomy can be done safely in-office. The procedure is fast and generally well-tolerated, after which most families report improved nursing or eating and happier babies. In older babies or toddlers, discuss with your child’s dentist or ENT whether release is needed for dental reasons.

Key resources: Trusted sources like the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association and child health organizations advise that good latch technique should be addressed first, and that many lip ties require no intervention. However, if symptoms persist, evidence from recent studies shows release of true lip ties often brings quick relief to both baby and mother. Always use a qualified pediatric provider for evaluation.

In conclusion, identifying and treating a in babies and toddlers involves careful assessment of feeding function, not just looking at anatomy. With proper diagnosis and, when needed, a gentle frenectomy, most children go on to feed normally and develop without issues. If you suspect a lip tie (primary keyword!), consult your pediatrician, an IBCLC, or pediatric dentist. Early recognition and treatment can make breastfeeding smoother and support your child’s growth and comfort.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What exactly is a lip tie?

A: A lip tie occurs when the tissue (frenulum) under the upper lip is unusually tight or attaches too far down on the gum, restricting lip movement. It can prevent the lip from flanging outward during feeding. In many sources, it’s called an “upper lip tie” or “maxillary lip frenulum restriction.”

Q: How can I tell if my baby has?

A: Look for feeding signs: a baby who can’t keep the upper lip forward on the breast or bottle, makes clicking noises while nursing, or seems to nurse continuously without satisfaction. On exam, a lip tie may be seen as a thick band of tissue under the upper lip that doesn’t allow the lip to lift easily from the gums. A healthcare provider can lift the lip and check if blanching (whitening) occurs on the gum, indicating tension.

Q: What does a lip tie look like vs normal?

A: In a normal baby, the upper lip moves freely, and the small frenulum is thin. In the frenulum is thicker and attaches closer to the gumline or palate. You might see the upper lip barely move or look tethered when the baby tries to suck. (The images above illustrate a typical upper lip frenulum and how a tight one can tether the lip.)

Q: Are lip ties common in newborns?

A: The exact prevalence of lip tie is not well established. Because almost all newborns have a labial frenulum to some degree, few are actually true lip ties needing intervention. Studies estimate 3–13% of babies have tongue tie; lip ties are thought to be less common than that. A recent parent survey found about 17% of surveyed parents had a child treated for it, but nearly all parents had heard of . In short, awareness is high, but only a smaller fraction have symptomatic lip ties.

Q: Will my baby’s lip tie go away on its own?

A: Mild lip ties often become less prominent as the baby grows, because the frenulum stretches naturally over time. By toddlerhood, most upper labial frenula do not cause issues and appear much thinner. If feeding is fine and there are no problems, doctors usually recommend observation.

Q: How is lip tie treated?

A: If needed, a pediatric ENT or dentist can perform a lip tie release (frenotomy/frenectomy). This simple procedure cuts the tight tissue under the upper lip. It is quick and typically done in-office, often with no anesthesia for newborns. The baby can usually feed immediately afterward.

Q: Is a lip tie release painful for baby?

A: Most infants cry more from the handling than from pain. The frenulum has few nerves, so discomfort is minimal. Many providers say babies show almost no pain during a lip tie revision. You should feel comfortable feeding right away.

Q: What is a frenectomy for lip tie?

A: A frenectomy (often used interchangeably with frenotomy) is the procedure to cut or remove the tight frenulum under the lip. It can be done with scissors or a special soft-tissue laser. The goal is the same: allow the upper lip to move freely.

Q: Are there risks or complications later in life?

A: If a significant lip tie is not treated, it may contribute to a small gap between the front teeth (diastema) or trap food under the lip, making brushing harder. Some pediatricians note a slight increase in upper front cavities if debris collects under a tie. Speech problems are rarely caused by lip tie alone. In contrast, leaving an untreated lip tie does not pose any acute danger if the child feeds and breathes normally. As the child grows, the frenulum usually thins out. Regular dental checkups will catch any spacing or hygiene issues early.

Q: What if my baby has both lip tie and tongue tie?

A: This is common. A baby with both ties may have more severe latch and feeding problems. In such cases, many providers will release both the tongue tie often even on the same visit, to maximize improvement. Each tie is released with the same simple procedure.

Q: When should I consult a specialist?

A: If your baby struggles to breastfeed (or bottle-feed) despite good support, or if you experience significant pain, latch issues, or weight concerns, talk to your pediatrician or a lactation consultant. They can rule out common causes and look for a lip tie. Many parents first see an IBCLC (breastfeeding specialist) who can spot lip ties during a feeding evaluation.

References

This article is based on current pediatric and lactation sources. In particular, Healthline provides a clear overview of symptoms and care. The open-access study Maxillary Frenulum What Parents Understand (OTO Open, 2023) highlights that lip tie definitions and interventions vary and rely mostly on parental concern. La Leche League notes the lack of evidence for clipping lip ties and emphasizes a normal frenulum becomes less obvious with age. A pediatric surgery report shows breastfeeding and weight gain improvements after isolated lip-tie release. We have also cited other expert sources and systematic reviews to provide a balanced, in-depth guide.